Maude Stanley, girls’ clubs and district visiting. A youth work pioneer who produced an early comprehensive youth work text – and helped to found the London Union of Girls Clubs.

Contents: introduction · work around the Five Dials · the Soho Club and Home for Working Girls · clubs for girls · conclusion · further reading and references · how to cite this piece

The Hon. Maude Alethea Stanley (1833-1915) was the third daughter of the 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley. Like many other women in her position, she devoted a significant amount of her time to social work, first as a district or parish visitor around the Five Dials, and then in youth work. However, the scale and scope of her work mark her out as a significant figure. She wrote the first substantial text on clubs for girls (1890) and made some efforts to facilitate inter-club links, establishing the Girls’ Club Union in 1880. It later became known as the London Girls’ Club Union and, along with the Federation of Girls Clubs (run under the auspices of the YWCA) and the Social Institutes Union, was reconstituted in the late 1930s as the London Union of Girls Clubs (now part of London Youth). Maude Stanley was also a Poor Law Guardian, a Manager of the Metropolitan Asylums Board (from 1884) and a Governor of the Borough Polytechnic (from 1892) (Bonham 2004).

She moved in very influential circles. Her younger sister Rosalind, for example, married George Howard (who was later a liberal MP and then became the 9th Earl of Carlisle) and was a great friend of William Morris (MacCarthy 1994: 410-11). Another, younger sister, Kate, married John Russell, Viscount Amberley, (the son of the former prime minister John Russell). Kate was a suffragist and was particularly concerned with women’s rights. Both John and Kate died young, and this meant their children spent time with their grandmother, Lady Stanley and their aunt, Maude Stanley (who was the remaining unmarried daughter). The youngest of these children was Bertrand Russell, and in his Autobiography, he describes visits to his grandmother.

I was frequently taken to lunch with her, and though the food was delicious, the pleasure was doubtful, as she had a caustic tongue, and spared neither age nor sex. 1 was always consumed with shyness while in her presence, and as none of the Stanleys were shy, this irritated her. I used to make desperate endeavours to produce a good impression, but they would fail in ways that I could not have foreseen… “How like his father!” she said, turning to my Aunt Maude. Somehow or other, as in this incident, my best efforts always went astray. (Russell 1967: 33)

Maude was also part of a significant circle of philanthropists, including Octavia Hill and Henry Solly. She lived in a family home close to the Houses of Parliament in Smith Square (No. 32 – the old rectory of St John’s) and, for a time, at 40 Dover Street (just off Picadilly).

Although Maude Stanley’s religious outlook was what might be described as ‘low church’, she shared with other members of her family a fairly broad-minded attitude towards religion (Bonham 2004). Bonham has described this attitude as pervading her life, ‘not least regarding her girls’ clubs’. Interestingly, her oldest brother became a Muslim (and the third Baron Stanley of Alderley) and a younger brother (Algernon) a Roman Catholic priest.

Maude Stanley died from a heart condition whilst at Alderley Park, Chelford, Cheshire (the family estate) in July 1915. She had been distressed by the outbreak of the First World War and had left London soon afterwards (Bonham 2004). The funeral was held at Alderley Park. Later, there was a memorial service at Smith Square. Her grave can be found in St Mary’s Churchyard, Nether Alderley, Cheshire [click for details].

Work around the Five Dials

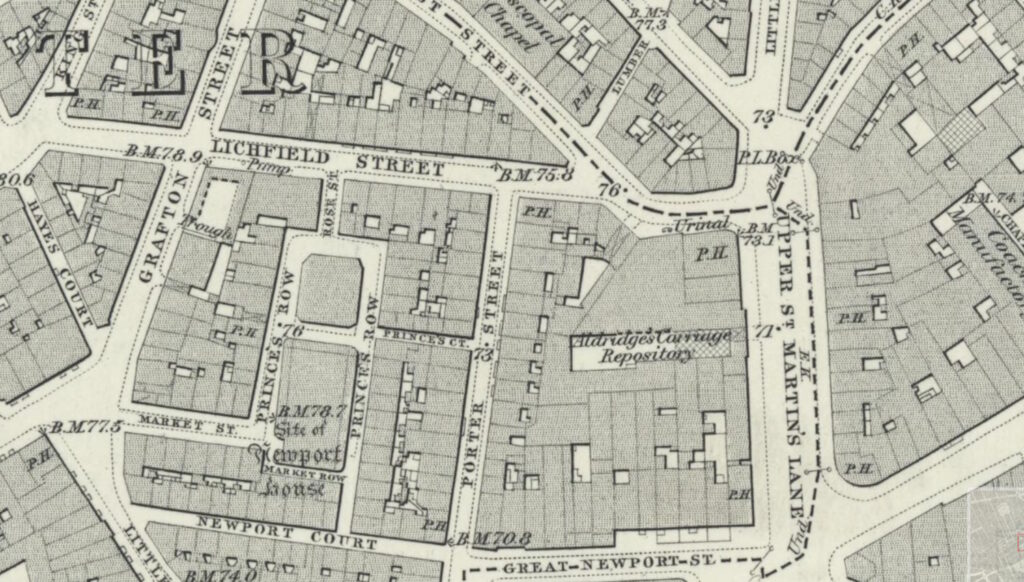

It is difficult to place The Five Dials as the area was completely redeveloped following the building of the Charing Cross Road and Shaftsbury Avenue (authorised in 1877, completed in the late 1880s, and known as the ‘Western Improvements’). One of the quarters Maude Stanley worked in was called Princes’ Row. It was just off the original Rose Street (which Garrick Street now runs across, in part). She describes the Row as ‘the poorest, the dirtiest, and the lowest houses that this part of London can boast of’ (Stanley 1878). The Improvements displaced around 5,500 people in this immediate area, which gives some idea of the overcrowding (Stedman Jones 1984: 171).

About five years ago I determined to try what I could do with these poor boys; who from their very civility to myself, I felt were open to the refining influence of a woman’s teaching. So in February, 1873, after knowing the neighbourhood for three years, I began a School on Sunday afternoons. I invited four boys to come, these brought others, and from that time to August, I had a varying number of from eight to twenty-five every Sunday. I began the School with a working shoemaker, who lived in the next street, and later I had a postman to help; but he was always called “Squint Eye” by the boys, from a personal defect and he never got much hold over them. The shoemaker’s temper and patience used to be sorely tried: as for mine, I felt it no trial, for the fact of contending with the determined mischief of some of the boys, had in it the delight of a fight, in which I was generally victorious. (Stanley 1878)

Chapter IX of Work About the Five Dials is on night schools (see the full text in the archives). It includes some interesting insights into the character of work with young men at this time, and reflections on an enduring question for philanthropists like Stanley – what is to be done to ‘reform’ or teach ‘idle and evil boys’? She was not that hopeful:

But of all faults the worst to contend with in a boy is idleness. If he will not work, you may give him chance upon chance; you may reprove, you may encourage, nothing will do them good. I have had a few cases of idleness where I have got a boy a place, but his laziness caused him to be discharged. I have come upon boys I knew of seventeen, who instead of working were playing at marbles in courts where they never expected to meet me. (ibid.)

For those who were prepared to learn and to work, something could be done. She includes various case studies of boys that succeed, and also makes the case, based on her experience of club work, that ‘there is a great need for places of harmless recreation for the immense working-boy population in London’.

The book was published with a commendation from Thomas Carlyle. Eagar (1953: 66) comments:

Like Bosanquet, to whom she was a feminine counterpart, she appealed for more workers to associate themselves with the Charity Organization Society, the Society for the Relief of Distress, Octavia Hill’s Women House Managers etc., and considered that the most effective way to help was to be a district visitor under the clergyman of the parish.

However, Maude Stanley, like many of her class, had rather dual standards (or hadn’t fully grasped the reasons for the poverty and distress she encountered). She was also a ‘landlord’ in the area and had houses that she admitted were ‘in a wretched condition’. Nevertheless, she charged what were then substantial rents, 4s. 6d. to 6s, and claimed compensation from the Metropolitan Board on the basis that all the rooms were occupied, although, as Stedman Jones (1976: 201) notes, she admitted this had not always been the case.

The Soho Club and Home for Working Girls

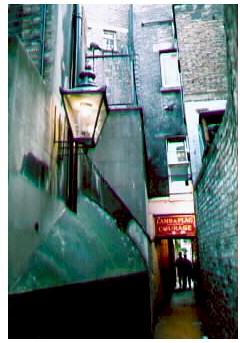

Maude Stanley founded the Soho Club (59 Greek Street W1) for Girls in 1880. It had originally begun in three rooms in Porter Street, Newport Market. A refuge had been set up in some old market buildings that also provided training and meals for boys. To the right of the door was a plaque unveiled in 1984:

59 Greek Street was built in 1883 as the Soho Club and Home for Working Girls. In the 1920s it became the Theatre Girls Club, a home for women working in the theatre and later a hostel for homeless women.

The building was opened by Henrietta Maria Lady Stanley (Maude’s mother) on June 30th 1883 (the plaque is on the left of the window above the front door). In some respects, the Club and Home resembled the earlier efforts by workers at the Colonnade Home and Club for boys. However, the nature of much girls’ club work at that time tended to emphasise relationships and gentle improvement so that girls may ‘ennoble the class to which they belong’ (Stanley 1890: 48). This could be contrasted with the talk of character-building and muscular Christianity that could be found around some boys’ work.

The club was open every evening of the week. Its programme included classes in drawing, French, singing, needlework, music, gymnastics and mathematics. The club had a library, canteen and a low-cost medical dispensary for its members. The short and long-term lodgings it provided for ‘Young Women engaged in business, and students’ could be had for between 3s and 7s 6d per week (depending on whether they slept in a dormitory or had a private room). This price included the use of a sitting-room, gas fire and clean bed linen (see Summers 1989: 123-4).

Exhibit 1: The Soho Club for Girls – Rules and notices

SOHO CLUB AND HOME

59 GREEK STREET, SOHO SQUARE

LONDON, W.

RULES AND NOTICES

Lodgings for Young Women engaged in business and students. Rent of Bedroom, including use of Sitting-rooms, is, with Gas Fire, washing of Bed-linen and Towels, 3s. and 4s. a week paid in advance.

Teachers or Students coming to London to pass Examinations can be lodged at 1s. per night.

Some Rooms at 5s., 6s. and 7s. each.

Breakfast or Tea, 21/2d. Dinner 6d. Supper 3d.

Anyone desiring Lodgings must obtain from the Matron the rules and a paper to be filled up with references.

Dressmakers and Needlewomen can be recommended from the Home to go out to work at ladies’ houses.

Entrance Fee to the Club, 1s. Subscription, 2s. per quarter, payable in advance by a member over seventeen years after one quarter’s membership. A fine of 2d. must be paid by members two weeks in arrears.

Members under seventeen years may pay their Club fees sixpence at a time.

No Member more than two weeks in arrears can be allowed the use of the Club.

The Card of Membership will not be given until a visit has been paid to the Candidate’s home by one of the Council. The badge is given after one year’s membership.

On Wednesday and Friday evenings, members may bring in a friend or their mothers to see the Club, on mentioning it first to the Superintendent.

A new member may be introduced to the Club by an existing member, by a member of the Council, or by, the Superintendent; but as some may wish to Join our Club who do not know any of the members, we shall be glad if they will come in any evening and the rules will be given to them.

No girl who has been a member of the Club and has left the Club can be admitted by a friend at a Soiree, or on any evening meeting of the Club, except with the object of rejoining the Club.

Each Lady of the Council will undertake the supervision of the Club for one month at a time, and will, during that month, visit new members and give them their cards of membership.

An appendix to Stanley (1890)

By 1889, according to figures in Clubs for Working Girls (Stanley 1890), there were 230 members ranging from 13 to over 21. With just 4 13-year-olds, there was an even spread of members (around 20 per year of age) through to age 20. Their occupations range from clerks and governesses through shop assistants and maids, to those working in factories and workshops. Looking back on the experience, Stanley (1890: 48) comments:

Slowly and gradually the girls have learned that order conduces more to the general wellbeing and comfort than disorder, and that culture and refinement are to a certain extent within their reach. They have realised that their club has been of inestimable value to themselves and that it has given them interests which have brightened their days, that through the club they have found friends who have helped them on in this life and shown them a higher life worth striving for.

Clubs for Girls

One of the striking features of Clubs for Girls (1890) is that it is very much a practice text. While Arthur Sweatman (1863), some 27 years before, exalted readers to become involved in club work, Maude Stanley is telling us about the experiences of workers and distilling this into guidance for those entering or newly engaged with the work. As a result, the book is enlivened by various stories and examples of practice:

Two bigger girls who were sitting happily at work. . . while a story was read to them, suddenly quarrelled about a thimble, and in a passion one girl threw the table over, the others mad with excitement began to act in the wildest, utterly indescribable fashion. . . . The horrified workers found the lower room in still worse confusion. Boys were banging at the shutters and door, the girls inside shouting and singing, and even fighting, slates, books and sewing being used as missiles. . . . One of the ladies went to speak to the lads outside, and one threw his cap in, and getting his foot in the doorway prevented the door being closed. Remonstrances were of no use. (Stanley, 1890: 195—6)

A year earlier, the first practice text around the experiences of boys’ club work had appeared (Pelham 1889), and it was apparent that there had been a substantial growth in the range and numbers of clubs that had been formed. There is much practical advice, and several elements stand out.

First, there is a firm belief that in starting and carrying out a club, ‘discipline and order are the first requisites’ (Stanley 1890: 18). This appreciation was drawn from her earlier work around the Five Dials (she makes some comments around this area in her 1878 book), and from her various visits to clubs.

Second, Maude Stanley saw the great importance of having ‘ladies’ in the club whom the girls could form relationships with:

Any helper in a girls’ club should, above all, have friendliness in her manners and in her heart; to be lively is a great advantage; quietness and decorum are attractive in a girls club as elsewhere, whereas pride or conceit is soon detected by them. We have heard of girls in a club who openly discussed the ladies who came to them, saying of one, “We don’t like Miss Ann, she is so stuck up! She gives herself such airs!” We need not add that such remarks should never be allowed – not silenced, but, quietly and apart, the girls should be reasoned with (1890: 22).

The final comment indicates something of the nature of the relationship that was deemed appropriate between ladies and working girls. A very similar set of qualities is seen to be necessary for the club superintendent if one is employed.

Third, we can also see an emphasis on self-government (after the pattern of Henry Solly’s working men’s clubs):

We feel a girl’s committee could really manage the club entirely alone, but as those who form the committee are all working girls, finishing their work at seven or eight, or later, in the evening, it would be too much to expect of them to give up so much of leisure as would be needed for the whole management of the books, registry of attendances, and payments of club fees. During our superintendent’s three weeks’ holiday last year the club was managed by the girls’ committee, and everything was satisfactory (Stanley 1890: 47).

The perspective from which Maude Stanley was writing reflected her social position – and her belief that upper and middle-class mores, habits and understandings were what working-class people should aspire to. As Blanch (1979: 105) has commented, working-class culture was a primary target for workers’ actions:

Children required salvation from the vices of their parent culture; . . . a second set of evils lay in the wiles of gambling, moral laxity, the ‘animal excitement’ of theatres . . . and the curse of drink. Clubs, then, wished to direct working-class leisure into respectable channels, with either a religious or military bias or both. They also existed to act as a focal point for loyalties. To their organizers, the closed nature of working class society evidenced a self-centred and selfish perspective on life.

While club leaders often asserted that they aimed to develop habits of self-reliance and independence in girls and young women, how this was interpreted and the reality of the work, on the whole, suggest rather different concerns. Thus, girls’ clubs, Snowdrop Bands and the Girls’ Friendly Society could be seen as attempting to fill a ‘gap’. Such girls would otherwise be influenced by their working-class peers and relatives:

Too much independence amongst young girls was a dangerous thing. It is significant that in most of the literature expounding the need for clubs and societies amongst adolescent girls, the working girl’s independence is perceived as ‘precocity’. Wage earning is believed to buy them a premature and socially undesirable independence. Further there is a strong assumption . . . that financial independence and sexual precocity go hand-in-hand. (Dyhouse, 1981: 113)

It was feared that the involvement of young women in the labour market and, consequently, their spending power, would tempt girls away from their allotted roles of wife and mother. If young women were ‘upwardly aspiring’, then what such organisations could provide them with was an experience in the ‘womanly arts’ so that they might influence their men:

If we raise the work girl, if we can make her conscious of her own great responsibilities both towards God and man, if we can show her that there are other objects in her life besides that of her gaining her daily bread or getting as much amusement as possible out of her days, we shall then give her an influence over her sweetheart, her husband and her sons which will sensibly improve and raise her generation to be something higher than mere hewers of wood and drawers of water. (Stanley, 1890: 4—5)

However, girls were not to get above their station. There were definite limits to the rite de passage: ‘we have not wished to take our girls out of their class, but we have wished to see them ennoble the class to which they belong’ (Stanley, 1890: 48). The bourgeois improvers could only ever offer a limited path between classes for both young men and women. They believed in and operated within a system which required a particular division of labour and which would have considerable difficulties in accommodating large numbers of young people wanting significant advancement. While the rhetoric of individual achievement came easily, it had to be contained within particular class, gender, racial and age structures: a woman’s place was in the home; to be British was to be best; betters were to be honoured; and youth had to earn its advancement and wait its turn.

Conclusion

Within the girls’ club movement, there initially appeared to be a concentration rather more on amusement than education or leadership. ‘We must turn to and provide for the girls that which their parents truly say they cannot provide – healthy and safe recreations, amusements and occupation for their leisure hours’ (Stanley, 1890: 14). Yet there were those who sought rather more. A few years later, Lily Montagu, working in the same area, desired to correct the ‘tendency to individualism and self-seeking which are produced by workshop life’ (1904: 246). She saw clubs stimulating ‘the members’ power of self-control and their sense of responsibility and widen(ing) the average conception of happiness’ (Montagu, 1904: 247). Emmeline Pethick reported on her experience of girls’ work in the 1890s:

The conditions, not only of the home, but of the factory or workshop had to be taken into account. It became our business to study the industrial question as it affected the girls’ employments, the hours, the wages, and the conditions. And we had also to give them a conscious part to take in the battle that is being fought for the workers, and will not be won until it is loyally fought by the workers as well. (Pethick, 1898: 104)

The effectiveness of the new provision was, as might be expected, limited. For example, while clubs might have exploited the need for recreation among working-class adolescents and combined this with their being vehicles for a conservative ideology, they did not necessarily attract large numbers. As White comments upon one Jewish club in the early 1900s:

The Butler Street Club, for example, sought ‘to lure girls from the streets, the Penny Gaffs and the musical halls’, but it succeeded in luring less than 200 girls away from pursuits unacceptable to the middle class. The stronger attractions of that culture of the streets and the musical hall and the cinema held greater sway over the youth of Rothschild Buildings than the given culture of the club. (White, 1980: 190)

For those involved, however, there could be considerable changes in their social circumstances and in their access to work.

Maude Stanley’s contribution was to bring together a series of lessons learned from working in girls’ clubs and to set them out in a way that was accessible and that opened up the work to many more people. She was also a significant organiser. The work undertaken by the Soho Club and Home, and the way she set about creating club networks, provided a major stepping stone to the organisation of the girls’ club movement (some years ahead of the boys’ club movement).

Note: this piece uses some material from Chapter 1 of Smith (1988) Developing Youth Work, see the informal education archives.

Further reading and references

Blanch, M. (1979) ‘Imperialism, nationalism and organised youth’, in J. Clarke et. al. (eds.) Working Class Culture. London: Hutcheson.

Bonham, V. (2004). ‘Stanley, Maude Alethea (1833–1915)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Pres., [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/45676, accessed 2 July 2007]

Dyhouse, C. (1981). Girls Growing Up in Late Victorian and Edwardian England. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Eagar, W. M. (1953). Making Men. The history of Boys’ Clubs and related movements in Great Britain.. London: University of London Press.

MacCarthy, F. (1994). William Morris. A life for our time.. London: Faber and Faber.

Montagu, L. (1904). ‘The girl in the background’, in Urwick, E.J. (ed.). Studies in Boy Life in our Cities. London: Dent.

Pelham, T.W.H. (1889). Handbook to Youths’ Institutes and Working Boys Clubs. London: James Nisbet.

Percival, A.C. (1951). Youth Will Be Led. The Story of the Voluntary Youth Organisations. London, Collins.

Pethick, E. (1898). Working Girls Clubs, in Reason, W. (ed.). University and Social Settlements. London, Methuen.

Ross, E. (2007). Maude Alethea Stanley in

Russell, B. (1967). The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell 1872-1914. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Smith, M. (1988).. Developing Youth Work. Informal education, mutual aid and popular practice. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Stanley, M. (1878).. Work About the Five Dials. London: Macmillan and Co. See extract in the archives. [Click to download full text from the Internet Archives/Google]

Stanley, M. (1890). Clubs for Working Girls, London: Macmillan. (Reprinted in F. Booton (ed.) (1985) Studies in Social Education 1860-1890. Hove: Benfield Press. [Click to download from The Internet Archive]

Stedman Jones, G. (1984). Outcast London. A study in relationships between classes in Victorian society. 2e, London: Penguin.

Summers, J. (1989). Soho, London: Bloomsbury.

White, J. (1980). Rothschild Buildings. Life in an East End Tenement Block 1887-1920. London, Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Acknowledgement: Opening image: Hon. Maude Alethea Stanley by Camille Silvy – National Portrait Gallery | nc-nd/3.0 licence. Picture: a young Maude Stanley – believed to be in the public domain – copyright expired.

How to cite this piece: Smith, M. K. (2001-2025). ‘Maude Stanley, girls’ clubs and district visiting’, The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education [www.infed.org/dir/maude-stanley-girls-clubs-and-district-visiting/. Retrieved: insert date]

© Mark K. Smith (2001, 2007, 2025)

updated: October 5, 2025